In Gaza, Rawan Fayad and Ajyal Association for Creativity and Development turn data collection into civic action

When the first bombs fell in October 2023, Rawan Fayad did not yet know that fear would become the dominant colour of her life. “It’s not the hunger, not the lack of electricity,” she says quietly. “The most catastrophic feeling was fear – the fear of losing your loved ones, your home, your memories.”

She had grown up in that same house on the border, the one her father, an engineer, built “with love, so his children would feel safe.” Her mother had guarded it fiercely after his death. When the war began, Rawan’s first instinct was to protect her mother. But the shelling did not stop. Eventually, the fear, “the kind that lives inside your bones”, forced them to leave. Days later, their house was gone.

“Home,” Rawan says, “is not a building. It’s the place that holds your memories, the people you love. When those are gone, you have to rebuild home inside yourself.”

She is thirty years old, a graduate in business administration, already working on psychosocial support programmes for caregivers. Her work felt steady, almost predictable. Then everything changed.

Displacement became the new geography of Gaza. Streets turned into shelters; families moved again and again, chasing safety that never came. “It felt like living inside a circle,” Rawan says. “Each time you move, you start from zero. But zero keeps moving too.”

“You learn that everything is a blessing,” she says. “Waking up in your own bed is a blessing. Washing your hands in a sink is a blessing.”

By the time she joined Ajyal Association for Creativity and Development, a youth-led civil society group, she was no longer the same person. “At first, fear paralyses you,” she says. “You can’t think, can’t plan. But when I saw what people were going through – widowed mothers raising families alone, people with disabilities cut off from medicine, families evacuated five, six times — something in me shifted. The fear turned into strength.”

The Ajyal’s team is young, most under 35, and they have had to become experts in improvisation. With their offices destroyed, they rebuild wherever they can — cafés, borrowed rooms, tents.

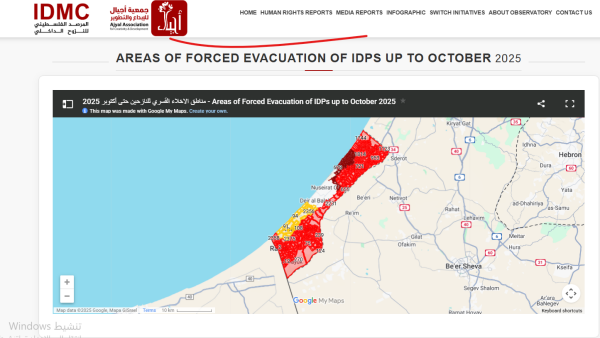

They came to the European Endowment for Democracy (EED) with a bold and ambitious idea: to establish the first Palestinian Observatory for Internal Displacement. Few organisations were as qualified to lead it. Based in Gaza, Ajyal – which means generations in Arabic – has lived through the experience it seeks to document. Its team understands, from within, the unreported challenges and rights violations faced by internally displaced people. Despite the devastation of war, Ajyal remains one of the few organisations that continue to operate, offering vital support to its community.

With EED’s backing, Ajyal trained journalists and human rights defenders to document displacement, gather testimonies, and tell stories of life in Gaza beyond the statistics. The Observatory has since gained recognition as the first Palestinian initiative dedicated to internal displacement, now regarded as a key independent source of data and insight on the crisis.

Rawan still remembers one of the first people they interviewed: a young woman fleeing the north with her brother. “She told me her mother had been run over by an Israeli tank. I had met her before, by chance, early in the war. Later, when our project began, I found her number again and called to check if she needed help. She gave her testimony. When she saw her story published, she said, ‘At least now someone will know we existed.’ That moment stayed with me.” Dignity is not abstract here. It’s survival.

That word, dignity, keeps returning. For Rawan, it’s what connects humanitarian aid and human rights, the practical and the moral. “People here are doctors, engineers, teachers,” she says. “They have plans, ambitions. And then, in one night, they were in tents. I want the world to know that Palestinians are not people who love tents. We are people who love life, who dream big, who deserve to live in dignity.”

Her ambitions for the Observatory go beyond documenting suffering. “Food and shelter are urgent,” she says, “but people also need education, mental health support, a reason to wake up. We believe in lifelong learning. ‘Leave no one behind’ isn’t just a slogan for us — it’s how we rebuild hope.”

The work is exhausting. Internet is patchy, transport dangerous. Yet the team keeps moving, driven less by optimism than by a quiet refusal to give up. “Courage can spread. When someone else stands up, you stand too.”

She dreams of one day expanding the Observatory to include more stories of those who rarely make it into the reports – single mothers, people with disabilities, displaced minorities. “I don’t like the word ‘marginalised,’” she says. “They are part of us. They are Gaza.”

When asked about her personal hero, she doesn’t hesitate. “My mother. She was both mother and father to us. She taught us to be humble, grateful, kind. I still hear her voice reminding me to stay grounded. Everything I do now is because of her.”

And if she could have one superpower? She laughs. “To go anywhere in the world in a second. Because here, under Israeli occupation, movement is our biggest dream. To be free, to see the world without anyone asking for permission. For others, that’s normal. For us, that’s a miracle.”

Rawan knows that her story – and the Observatory’s – will never capture the whole truth of Gaza. But perhaps that is not the point. “Every statistic has a face,” she says. “Every displaced person has a heartbeat.”

When the war paused, briefly, she and her team took what she calls “a long, shaky breath.” It was not peace, but a moment to look around and count what was left. “We had lost our offices, our homes, some of our families,” she says. “But we still had our purpose. And maybe that’s enough to start again.”

In Gaza, purpose is resistance, and hope is an act of rebuilding – over and over again. “Maybe,” Rawan says finally, “this is how we survive fear. By turning it into something that helps someone else.”

This article reflects the views of the grantees featured and does not necessarily represent the official opinion of the EED.