“The word Jummar, which means palm heart in Arabic, is rooted in the heart of Iraqi society and it symbolises what we wanted to do. As a media platform, we are addressing social issues at the heart of Iraqi society,” says the team of the online media outlet Jummar or ‘palm heart’ in Arabic.

It might seem odd to call a media outlet after an edible item, but this naming was an obvious choice for Jummar’s founders, Haneen Naamneh, Omar Al-Jaffal and Aida Al-Kaisy.

Launched in October 2022, Jummar is forging new ground for Iraqi independent media to respond to the lack of a creative and ethical independent media in Iraq that goes beyond the usual topics and stereotypes on Iraq, for example corruption, militia and the endless conflict.

“In Iraq today, most media outlets are not trained to ask questions. They publish the information they’re given by the government, militias or NGOs. They don’t address societal issues, or women and gender issues, and there are very few media outlets focused on issues of interest to young people,” says Omar, Jummar’s editor-in chief.

“It was important for us to support women and men journalists, whether early career or established, to activate their social imagination and write about the experiences that they have witnessed and lived or practices and phenomena in Iraq that they, even before their readers, wanted to learn about”, explained Haneen, the director of Jummar and one of its senior editors.

Since its launch, Jummar has been present and active on social media, in particular on Instagram where many young Iraqis are active. “We want Jummar to be young people’s go-to source of information,” explains Ahmed Hayderi, the outlet’s social media manager.

It was the mass protests of 2019, the largest protests in Iraq’s modern history, that prompted the launch of this new media. Jummar launched on the third anniversary of the 2019 protests.

“Young people make up over half the population of Iraq. They are a generation without hope. They are frustrated by the collapse of the state, mass corruption and a general lack of reliable information,” explains Omar.

Jummar has quickly become highly popular among its growing community of followers. “We see this through their engagement on our posts. Our most popular posts are about human rights issues and women’s and gender rights. Our infographics are hugely popular,” Ahmed explains.

The Jummar website includes opinion pieces, features, long reads and infographics in Arabic and English. It has also recently began providing access to research and content on key topics of interest to Arabic speaking Iraqis, much of which is originally published in English and was previously inaccessible to this audience.

The editorial team is engaged in an ongoing dialogue with its journalists. “We asked them to pitch us ideas based on our editorial policy – stories on everyday life from a from social perspectives. We encouraged them to write about issues not usually covered. About the environment, economy, the education system,” they note.

“Journalists have written about what does it mean to be a drug addict seeking rehabilitation, a farmer forced to immigrate as a result of drought, a women taking public transportation in southern Iraq, and about the experience of urban life, like what it’s like to live alone as a woman in the city, or in a city with hardly any trees, like Baghdad,” they continue.

A recent series on women’s experiences of summer in Iraq was hugely popular, and Jummar are now planning a new series focusing on labour and unemployment, another underreported topic in Iraq.

Omar notes that writing about gender is vital at this time. 49 percent of Iraqis are women, yet politicians and militia recently announced a ‘war against gender’, perceived as a western concept which threatens traditional Iraqi culture and tradition.

Many of Jummar’s contributors are women and queer people, some with no previous journalistic experience, others writing under pseudonyms. “Jummar constitutes a safe space as we as editors work with them to write in their own unique voice,” Haneen explains.

From the beginning, the team knew that the 2003 anniversary of the invasion of Iraq would be a focus for their work, as it was marked during the first months of Jummar’s launch.

“We wanted to influence how this anniversary was marked in Iraq and beyond, and to bring social experiences and memories of that time to the young generation. We asked journalists and individuals to write about their experiences as children or teenagers and to reflect on its impact on their present,” says Haneen.

This proved a success for Jummar, helping them build a profile within Iraq, amongst Arab speaking media and internationally. Over the past 10 months, they have collaborated with titles including The Guardian, Courrier International, MERIP, Assafir Al-Arabi and EED partner Al-Jumhuyriya.

With a remote team based across Europe, the Middle East and Iraq, Jummar believes that they can make a long-term change to the media scene in Iraq.

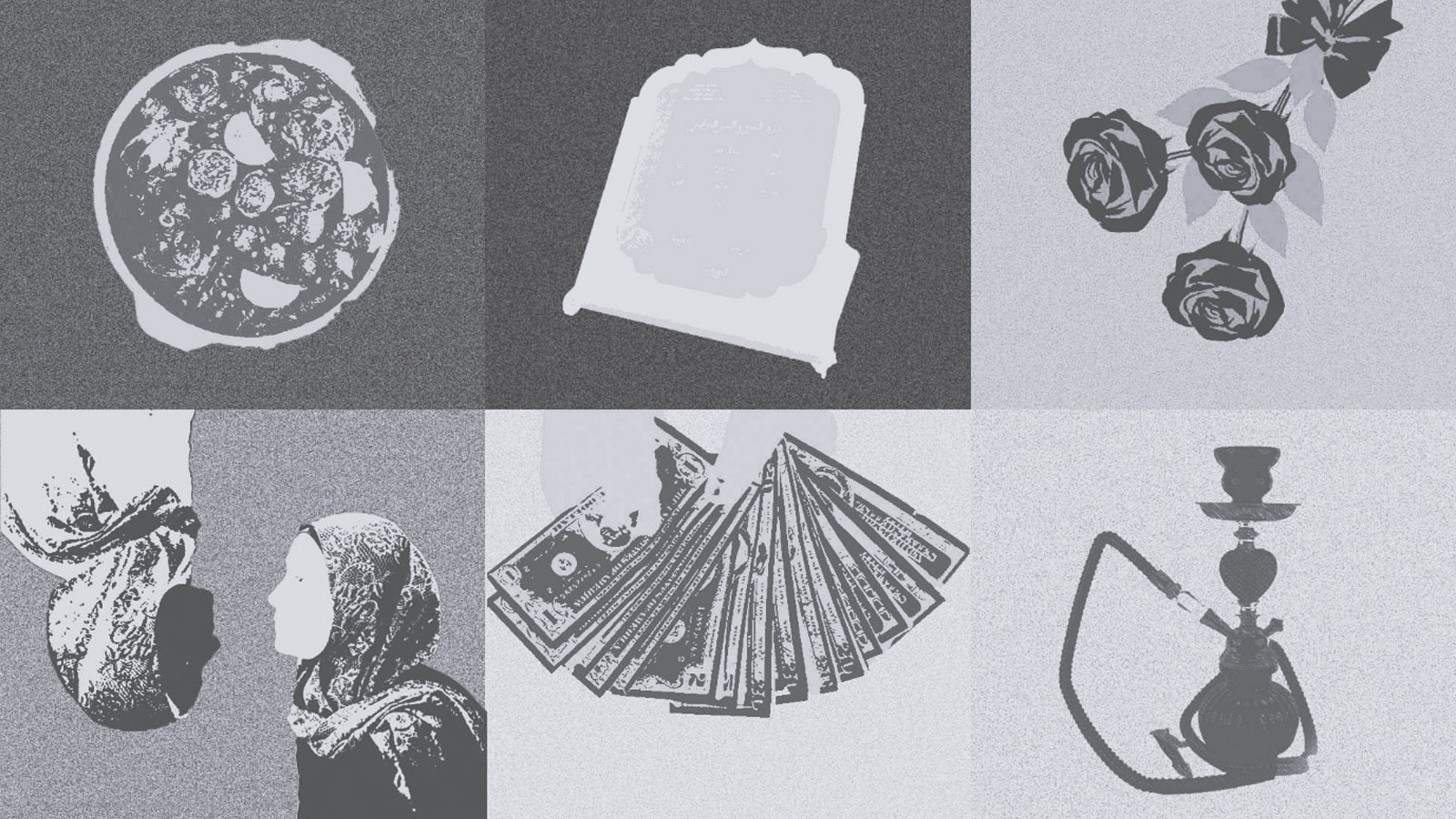

But Jummar is not just about ethical journalism, but also about creativity and artistic expression. Each text is accompanied by unique designs, that have become a core part of Jummar’s (visual) identity. Cultural production in general, and poetry in particular, are part of how Jummar engages and reaches out with society.

Iraqis are known across the Arab world for their love of poetry and Omar himself is a poet. Each day, Jummar begin by posting a short poem. “Now this poetry ritual is like our signature,” relates Omar.

This article reflects the views of the grantees featured and does not necessarily represent the official opinion of the EED.