“Our main goal is to provide the local community with the same information regardless of their ethnicity. We translate everything into Arabic, Kurdish and Turkmen and we publish in English, for those abroad who are interested in news from the region,” says KirkukNow’s Editor-in-Chief Salam Omer.

KirkukNow operates in one of the most complex areas of Iraq, which includes parts of Kirkuk, Nineveh, Diyala and Salahaddin governorates in Northern Iraq, a region that is home to, mainly Kurds, Turkmen, Yezidis, and Assyrians ethnic groups. These minorities suffered decades of forced Arabisation under the Baath Party rule.

After Saddam Hussein was ousted by the US invasion of Iraq, sporadic clashes continued in the region, which was occupied by ISIS in 2014. There were countless human rights abuses at that time, the most infamous of which was the genocide of the Yezidis.

Today, many areas of Northern Iraq remain a disputed territory, with the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) controlling parts of the region and many parts contested between the central government in Baghdad, and the KRG. Media access is particularly difficult, and the local media landscape is incredibly fragmented, with most people in each community only reading the news - often biased and incomplete versions of the news - in their native language.

EED partner KirkukNow is a notable exception in this media landscape. Operating since 2011, it takes the approach of multilingual reporting to build dialogue between communities within the disputed territories.

A challenging start

“At the beginning, things were very difficult: it was hard to find competent journalists in touch with the different communities, and everyone from all sides accused us of being biased in favour of one ethnic group or another,” Salam recalls.

Today, eleven years after its inception, KirkukNow has a staff of 10 people from different ethnic groups, and a wide network of reporters across Iraq. They have built a reputation as a credible and impartial source of news about the disputed territories, and many foreign media regularly contact them to better understand the situation in northern Iraq.

The team has had to navigate very complex situations over the years. At the peak of its expansion, ISIS controlled 70 percent of the territory where KirkukNow operates. “At the time, we asked many of our journalists living in areas occupied by ISIS to stay safe and not work,” recalls Salam. Many insisted on continuing to work as they felt it was their duty to report from the occupied regions.

A dangerous country for journalists

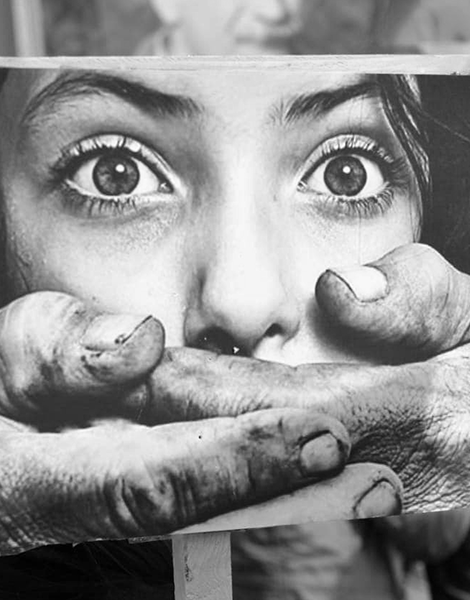

Even today, with ISIS long gone, Iraq is a dangerous country for journalists. It is placed at 172nd place (out of 180) in Reporters Without Borders’s World Press Freedom Index and 22 journalists have been killed there since 2003, and no one has been held accountable for their deaths.

KirkukNow is registered as a media outlet with both the central government and the KRG allowing its journalists to work throughout the region. The team also invests time in having good relationships with local authorities, “Except with extremists - that is simply not possible,” says Salam.

Commenting on the challenges faced by journalists in Iraq, he notes that while, “freedom of the press is enshrined in the Iraqi constitution, in practice, the government has no real vision. It doesn’t understand the role of journalism and why it is important for the community, especially for those groups who are marginalised and cannot be heard.”

This is why KirkukNow provides extensive coverage about underprivileged groups, from religious and ethnic minorities to women.

“Today, there is little objective quality content about minorities in Iraq. They are often presented as problems, while we present them as people. We write factual, high-quality content, to counter the misinformation and disinformation about them,” he says.

An award-winning model imitated by other local media

Salam emphasises that KirkukNow approaches journalism as a tool to achieve peace and democracy. “Conflict parties always see the media as an enemy in times of war. They need propaganda, not quality. They thrive on misinformation, and they don’t want the local community to know the truth. That’s why it’s important for journalism to give a voice to marginalised communities.”

This vision is paying off. In 2020 KirkukNow won an award from Internews for the best coverage of women’s rights issues in Iraq, and last year received a prize from a local radio station and the National Endowment for Democracy for the best human right journalism in the region, following the publication of two articles, the harrowing story of a child forced to fight alongside ISIS, and a report about freedom of expression and prosecution of journalists in Iraqi Kurdistan.

KirkukNow is also paving the way for other local media organisations to cover previously underreported topics. Several other local media outlets have told Salam that KirkukNow gave them the courage to write about minority and women’s issues.

Salam and the KirkukNow team are pleased with the progress so far, but they are committed to continue to push for change. “We want to provide Iraqi citizens with high-quality reporting so that they can make informed decisions on their future, on elections, and on all the issues that our country has to face,” he says.

This article reflects the views of the grantee featured and does not necessarily represent the official opinion of the European Endowment for Democracy, the European Commission or any other European State or other contributors to EED.