The day EED interviews Ma’an Abu Taleb and Mariam Elnozahy of the online music magazine Maazef, Abu Taleb is speaking from London and Elnozahy from her apartment in Cairo. This is normal life for the Arab world’s premiere music magazine.

Since its establishment in the months following the 2011 Arab Spring, the editorial and journalistic team of Maazef have been scattered around the world from Amman to Tunis, Cairo to Beirut, Berlin to London, where they write and publish content that is avidly consumed by hundreds of thousands of young Arabic speaking music-lovers throughout the Middle East and North Africa. The Covid-19 pandemic has barely changed the way they go about their business.

The Jordanian born Abu Taleb relates that he and the other founders of Maazef had long harboured ambitions of establishing a music magazine for the Arabic world and he recalls the 2011 revolution as a ‘slap in the face’. Music formed an important backdrop to the Arab Spring, with rap the soundtrack of the Tunisian revolution, and there was a sudden eruption of what he describes as exciting new political music throughout the region.

But no one could write confidently about this wave of new music. Journalists lacked the knowledge and skills and when they did write anything, they tended to frame the music in what he describes as a patronising narrative of Arab victimhood.

Confronting the myths of Arabic music

“There was no coverage of this new music as something purely creative. There’s a long tradition of Arabic music, but it tends to be spoken about in terms of a few standard myths – so the golden era of Arabic music and the demise of traditional Arabic music. We wanted to confront those myths and to go beyond them. For instance, ‘sha’abi’ music – a style of music that emerged in working class Egypt – is often denounced on moralistic grounds. We wanted to come up with a way of analysing the music of young people’s lives in a critical discursive way, discussing its successes and its failures,” explains Abu Taleb.

“For us it was important to present a new way of thinking about music. We wanted to write in the language of Arabic youth, not using our parents’ language, or the language of the West. We wanted to bring together a team of young Arabic writers with a fresh perspective and approach,” he continues.

Over the past few years, Maazef has become known for its coverage of Arab youth music culture and for the way it uses music as a medium to address issues of interest to young people, such as politics, economics, gender, homosexuality and other societal issues. The website includes longform features, album reviews as well as shorter pieces on the latest releases. Maazef covers all popular current music styles, such as ‘Mahraganat’ or Electro Sha’abi, as well as the trap scene in Palestine. Its website and social media pages are now accessed by up to 350,000 young people from throughout the Middle East region and beyond each month.

Addressing contentious issues

Abu Taleb notes that the online magazine’s success is in no small part due to its willingness to take on contentious issues. It was one of the few outlets that criticised the Jordanian government’s ban on a concert by the popular Lebanese band Mashrou Leila, whose lead singer is openly gay.

Recently, it carried a feature on what is referred to as Jihadi music of ‘nasheed’. As he describes it, the magazine’s journalists wanted to dig deeper than the usual condemnatory articles on this style of music. “We wanted to understand where Jihadi music comes from, who listens to, why people listen to it. We wanted to analyse if it is related to Islam or not, and how it has been adopted by terrorist groups and the Islamic State,” he relates.

As part of this reportage, the magazine’s team developed playlists of the most popular Jihadi songs and shared them with five popular musicians requesting them to devise musical responses. They then released what they dub their ‘Jihadi Mix Tape’ where these musicians took well-known Jihadi songs and remixed them, in one case changing the story of a Jihadi suicidal mission song to one of bidding farewell to a friend or a lover.

Another recent equally contentious dossier was entitled ‘The Music of God’, when the website’s journalists investigated Islam’s relationship with music, and the relationship of Qur’an readers and music. This report caused quite a furore when it was published, with both the Egyptian and Saudi authorities warning the magazine’s editors to stay within their mandate of writing about music. The online magazine was also hacked shortly after the publication of this report.

Collaboration with Boiler Room

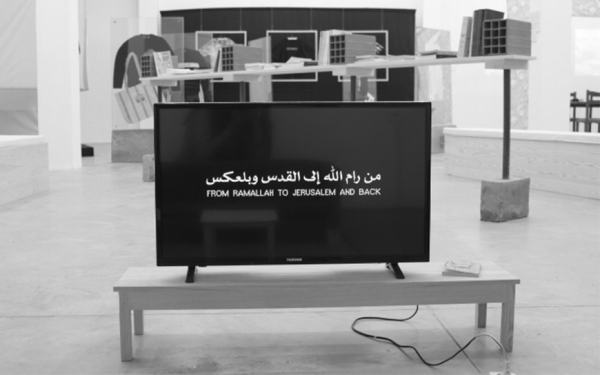

Elnozahy, who describes herself as the edition’s business development manager, notes that it was Maazef’s 2019 collaboration with the online music platform Boiler Room in a 2018 video about the TRAP scene in Ramallah that brought it to a more global audience.

This half-hour long video documents the hip hop, trap and techno music scene in Palestine that is fuelled by political restrictions and aims to build bridges between all Palestinians through a shared sound and identity. The 25-year old Palestinian rapper Shabjdeed is currently one of the biggest stars of this movement. A recent interview and article with Shabjdeed was viewed over 114 thousand times. Another feature, the Ma’adi Cyhper, was viewed over 3 million times.

Maazef also recently extended its activities to organising large music events through the Middle East and they organised for Shabjdeed to play a tour of gigs throughout the region. Elnozahy notes that for this prominent Palestinian rapper, the politics of his identity does not define his music.

“He is a rap artist like any other rap artist. His music is for art. He is not seeking to be political or subversive. The media too often shoehorns Palestinian artists into simplified narratives of cultural resistance. He is just inspired by his daily life in Ramallah. He wants to normalise his life and to do art for art’s sake,” she explains.

Writing school for young music journalists

Abu Taleb and his colleagues realised early in the life of Maazef that there were few journalists with the skills to write about the contemporary Arabic music scene, and in 2013, they decided to found a music writing school to train young music journalists.

This writing school is now open to young people from throughout the Middle East and it is run online across a period of two months. It generally recruits a cohort of 12 students, who are accepted onto the programme if they can demonstrate a passion for music, a sense of curiosity and strong Arabic-language writing skills. They prefer young people with no previous journalism experience.

The programme’s curriculum is fluid, informed by the evolving music scene and focused on teaching writing techniques. Students are also taught how to address sensitive politics and societal issues through the medium of music. At the end of two months, two or three of the most promising students are employed by Maazef to write and edit content.

The Covid-19 pandemic has of course affected some of Maazef’s immediate plans. They were hoping to open a new office in Tunis this year. They were also hoping to run further music festivals and conferences in the region, but these are now also on hold.

Elnozahy describes these extensions to the magazine’s activities as an important part of their ambitions to become financially independent of donors within the next two years. Maazef is also seeking more corporate sponsorship opportunities and is hoping to shortly launch a merchandising service. Their YouTube channel is also gaining more subscribers. They will also shortly launch a new radio service, that will generate significant new traffic to the website, and they also plan to monetise this traffic.

But for now, the core music journalistic work of Maazef remains unaffected and the magazine’s team continue to work remotely producing quality content for its readers.

This article reflects the views of the grantees featured and does not necessarily represent the official opinion of the EED.