From the balcony of Karşı Sanat, a contemporary art centre above Istanbul’s main central İstiklal street, you can see Galatasaray Square. Once a regular stage for demonstrations and political action, the Square is now host to a permanent police presence.

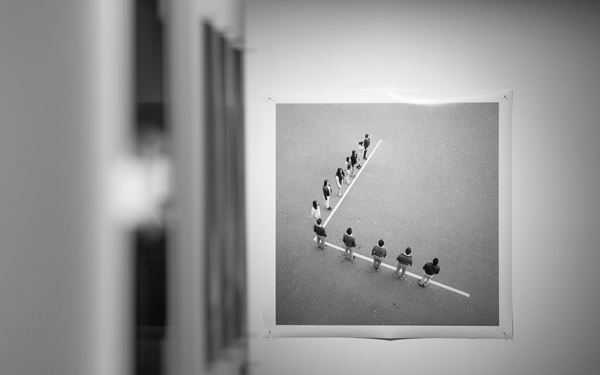

The noise of protests can be heard, but not from outside; they are coming from a video installation in the gallery, showing over layed protests scenes from earlier years. The work is part of Fermentation, an exhibition by young photographers from across Turkey.

Karşı Sanat operates as a collective, and as well as an exhibition space, regularly hosts events, debates and workshops. It is run by a mix of artists, teachers and academics, all of whom are passionate about giving artists a space to express themselves freely on sensitive topics while being accessible to all kinds of people, including those who wouldn’t normally go to exhibitions.

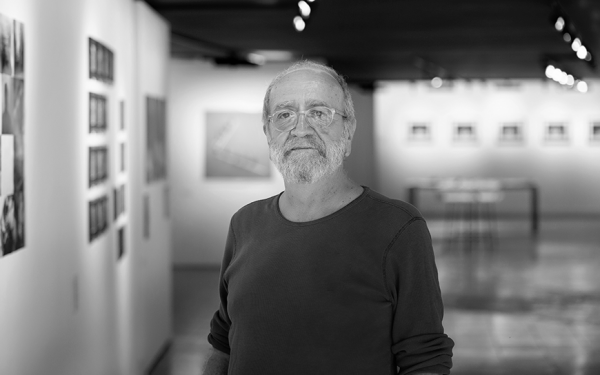

The roots of Karşı Sanat go back to the 1970s when artist Feyyaz Yaman founded an artists’ studio. Several names and locations later, Karsi Sanat found its home in the heart of Istanbul.

“Here we are at the centre of the centre – a memory space. Iconic photos were taken from this balcony,” says Yaman. “Galatasaray Square is now occupied – we are reclaiming this street as a first political act.”

Art under pressure

While Yaman says it has always been an issue for artists in Turkey to find venues to express themselves, “being political under the cloak of art doesn’t work as in the past.”

“The main issue is artists are really afraid – they have the desire to do things but all the mechanisms for doing so are under pressure,” explains Yaman. “Of course there are certain risks but they are afraid to take them.”

Yaman is all too aware of the risks of speaking your mind in Turkey – friends, as well his own brother, have disappeared in the past decades for their political beliefs or associations. “The state is never happy about free art,” he says.

More recently, in 2015, an exhibition in Karşı Sanat of archive material about the 6-7 September 1955 riots targeting the Greek and Armenian minorities attracted violence of its own. The exhibition was attacked and damaged, despite a significant police presence outside. Four years later only one perpetrator has been convicted.

“Now we always have a table for police officers to have their tea,” jokes Orhan Cem Çetin, the centre’s coordinator and a self-taught photographer, who also teaches art theory at a university.

Karşı Sanat has always tried to be self-funding, eschewing politically connected or conditional sources of funding in order to maintain its intellectual and artistic independence. The current economic crisis has put a strain on finances however, and their premises lay unfurnished for months until they received a grant from EED, satisfied that the funding came without strings attached.

Art across the generations

One of Karşı Sanat’s strengths is its inter-generational approach, encouraging collaboration between experienced artists and academics and emerging artists. “We always try to follow young artists,” explains Çetin. “There are lots of artistic groups around the country.”

Earlier this year they ran a summer school, bringing young artists and theatre actors together to collaborate on an experimental production in a huge, empty trade fair space.

They also involved academics who lost their jobs after signing the 2016 “petition for peace”, that pushed for peace between the Turkish and Kurdish forces. With backgrounds in gender studies, theatre, aesthetics and politics, Karşı Sanat gives them an opportunity to continue their work and engage in projects.

Other activities have included a collaboration with textile workers in a textile factory and a project about a prison in Southeastern Turkey notorious for torture.

An open space

Reinforcing its identity as a unique space where expression and politics meet, the Karşı Sanat team is always happy to collaborate with other organisations. “We strive to build direct mutual relations and bonds with anyone interested in what we are doing here,” says Eda Yigit, a specialist in social memory and oral history. “All activities carried out at Karşı Sanat are critical in terms of ‘history of the present’ or ‘recording the current issues’.”

“We try to act quickly – we are not strict about future plans,” says Ezgi Bakçay, a university teacher in aesthetics and politics, and another member of the Karşı Sanat team. “For example, when an exhibition on women authors needed a venue, we pushed our own event in order to have space for them.”

Walking around the exhibition, the interplay of art, politics and aesthetics is everywhere to be seen – one work plots early morning photographs of the empty sites of Istanbul’s past terrorist attacks; another series of photos by a former soldier questions life after the military. And on the way out, before going back down to bustling Istiklal, you pass a video of hundreds of mesmerising black and white stills taken on the early morning commuter train across the city.

A reminder, perhaps, that even under pressure, life – and art – goes on.

This article reflects the views of the grantees featured and does not necessarily represent the official opinion of the EED.