It was in 2013 during a wave of violent protests that a group of Sudanese telecommunications engineers from both inside and outside the country started to think about a technical solution to circumvent media censorship. With national newspapers editions seized, journalists arrested and Internet access cut across Sudan, there was no media coverage on unfolding events.

One of the engineers, Faisal Nourelhuda, realised that satellite TV was the solution. This is a medium particularly suited to Sudan, where nearly 80 percent of the population of 40 million own satellite dishes, and where TV is a common social activity, with people watching television in cafes, restaurants and refugee camps. In 2015, Husam Mahjoub, Ammar Hamoda and others took part in a short-lived satellite TV broadcasting venture, Sudan Bukra – or Sudan Tomorrow - that folded due to lack of funding.

Once again in December 2018, with Internet shut down, no national media reported on country-wide protests. As the 2018 crisis intensified with the ongoing media black-out, a diaspora-led group led by Sudanese medics contacted the Sudanese Professional Association (SPA), an alliance of independent trade unions and bodies, who put them in touch with the group that had launched Sudan Bukra in 2015.

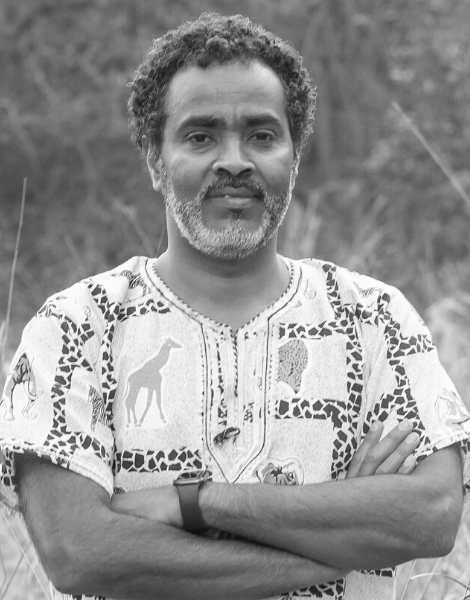

After a flurry of fundraising and crowdfunding, Sudan Bukra was launched for the second time in 2019 and began broadcasting from a European satellite provider. This was a deliberate choice, according to Mahjoub.

Speaking from his home in Austin, Texas, he explains, “The security services had the capability to intercept communications and block broadcasting. We needed to broadcast on a provider that was outside the Sudanese government’s control. Even after the revolution, it became clear that it would take time to dismantle Bashir regime’s infrastructure, and we continued to operate cautiously.”

Giving a voice to all Sudanese

From the beginning Sudan Bukra was conceived as a media that would give voice to all Sudanese people, including youth, women and minorities and it was founded on the premise of democratic principles.

“We wanted the channel to be open to everyone, no matter who they were, if they lived in refugee camps, or they were intellectuals, even if their mother tongue was not Arabic,” Mahjoub explains.

He admits that the channel faced shaky times after the fall of the regime of Omar al-Bashir, and it took them a few months to establish a presence in Sudan, supported by a globally-based team of volunteers.

It was in the immediate aftermath of the 3 June 2019 massacre that Sudan Bukra came into its own. On that day hundreds of peaceful protestors were killed and hundreds more were injured when security forces violently dispersed a three-month-long sit-in at military headquarters in Khartoum. Once again, Internet was shut down and Sudanese-based media heavily censored. Sudan Bukra was the only channel providing unbiaised reporting on events on the ground 24/7.

“Protestors and the general public relied on us during those traumatic days. We began to see how we could use Sudan Bukra as a tool for the Sudanese people,” says Mahjoub.

It was shortly after this that EED began to fund the station’s operational costs. “We were able to cover the rent of the satellite through diaspora donations for a period, but as the regime fell, there was less money available. The EED grant came at just the right time,” he says.

A variety of programme content

Sudan Bukra has worked with other partners from the outset. As well as producing their own programming, they rebroadcast video content from other individuals or organisations who share their values, including young producers who usually post on YouTube. They also work with other networks that provide material from throughout the country and are involved in the editorial team, such as Ayin Network, Sudan Revolution Radio and Jor3at wa3y.

Today, the station broadcasts 24/7 and it has a number of highly popular programmes. During the crucial revolutionary days, Ibrahim ‘Showtime’, a Facebook star and influencer from Darfur, was one of the most popular presenters.

Programming includes shows focused on political analysis and commentary, interviews with prominent Sudanese – a show presented by Mahjoub – as well as sports and culture content.

Living up to brave ambitions

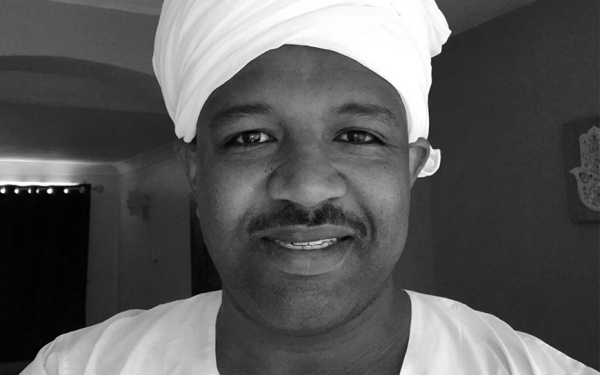

Asked if Sudan Bukra has lived up to its ambitions, both Mahjoub and Hamoda, who joins the conversation from his home in London, believe that the station is making a real difference.

“People trust our channel. We show the real Sudan. We show people’s lives: in the streets, on farms, in workplaces.They recognise themselves on screen. We are not an elite channel, as is the case of so many other media. Many prominent journalists and commentators have even written on the influence of Sudan Bukra – some even call us the channel that toppled al-Bashir,” says Mahjoub.

Today, the channel is building a Khartoum-based team who will take over the day-to-day running of the station from the currently globally-based team. They are also appointing a new editorial board and they are also focused on building networks of reporters throughout the country. The stations’ founders also have ambitions to launch an FM radio station in Sudan, as radio offers access to an even wider audience, although both men admit this is a complicated venture.

Hamoda warns, however, that it is still early days for Sudan and that much work lies ahead. “This transitional period is complicated. While the heads of government and state media institutions may have changed, the culture of these organisations remains unchanged as most other staff remain in place. The media sphere is easily manipulated, yet media is at the frontline of democracy,” he says.

He believes that Sudan Bukra offers a model for the future for other organisations and for Sudan – as an organisation operated and financed on a democratic basis, open to all Sudanese, collaborative and free from influence.

With the governance model of the station now overhauled, Sudan Bukra is ready for the next chapter in its life, and it is determined to be sustainable. “We are fighting giants, from both a technological and financial point of view. We need to build the capacity of our teams and constantly improve our technology to survive. But we want to be and we will be resilient,” he says.